If Vaccinations Are So Effective How Come Peoole in Their 50s Need to Get It Again?

As COVID-19 vaccination rates pick up effectually the world, people have reasonably begun to inquire: how much longer will this pandemic concluding? It'southward an issue surrounded with uncertainties. Merely the once-popular thought that enough people will eventually gain amnesty to SARS-CoV-2 to block well-nigh transmission — a 'herd-immunity threshold' — is starting to look unlikely.

That threshold is more often than not achievable merely with high vaccination rates, and many scientists had thought that once people started beingness immunized en masse, herd immunity would permit society to return to normal. Nearly estimates had placed the threshold at 60–70% of the population gaining amnesty, either through vaccinations or past exposure to the virus. But equally the pandemic enters its second yr, the thinking has begun to shift. In Feb, independent data scientist Youyang Gu changed the proper noun of his pop COVID-19 forecasting model from 'Path to Herd Immunity' to 'Path to Normality'. He said that reaching a herd-immunity threshold was looking unlikely because of factors such every bit vaccine hesitancy, the emergence of new variants and the delayed arrival of vaccinations for children.

Gu is a data scientist, but his thinking aligns with that of many in the epidemiology customs. "We're moving away from the idea that nosotros'll hitting the herd-immunity threshold and and so the pandemic volition go away for good," says epidemiologist Lauren Ancel Meyers, executive director of the University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modeling Consortium. This shift reflects the complexities and challenges of the pandemic, and shouldn't overshadow the fact that vaccination is helping. "The vaccine will mean that the virus will start to dissipate on its own," Meyers says. But as new variants ascend and amnesty from infections potentially wanes, "we may find ourselves months or a yr down the road withal contesting the threat, and having to deal with future surges".

Long-term prospects for the pandemic probably include COVID-19 becoming an endemic disease, much like influenza. Just in the near term, scientists are contemplating a new normal that does not include herd amnesty. Here are some of the reasons behind this mindset, and what they mean for the next year of the pandemic.

It's unclear whether vaccines prevent transmission

The key to herd immunity is that, even if a person becomes infected, there are too few susceptible hosts around to maintain manual — those who have been vaccinated or accept already had the infection cannot contract and spread the virus. The COVID-19 vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech, for example, are extremely effective at preventing symptomatic disease, just information technology is still unclear whether they protect people from becoming infected, or from spreading the virus to others. That poses a problem for herd immunity.

"Herd immunity is just relevant if nosotros accept a transmission-blocking vaccine. If we don't, so the but way to go herd immunity in the population is to give everyone the vaccine," says Shweta Bansal, a mathematical biologist at Georgetown University in Washington DC. Vaccine effectiveness for halting transmission needs to be "pretty darn loftier" for herd amnesty to matter, she says, and at the moment, the data aren't conclusive. "The Moderna and Pfizer data look quite encouraging," she says, but exactly how well these and other vaccines cease people from transmitting the virus will have big implications.

A vaccine'due south power to cake transmission doesn't need to be 100% to make a difference. Fifty-fifty lxx% effectiveness would be "amazing", says Samuel Scarpino, a network scientist who studies infectious diseases at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. But at that place could still exist a substantial corporeality of virus spread that would make information technology a lot harder to break transmission bondage.

Vaccine curl-out is uneven

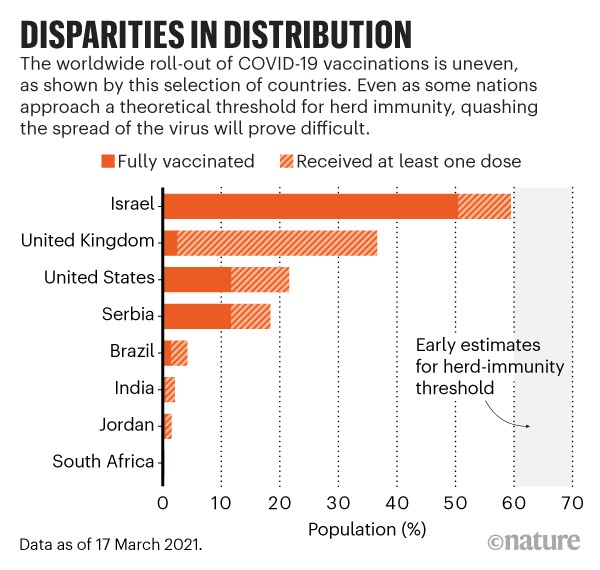

The speed and distribution of vaccine gyre-outs matters for various reasons, says Matt Ferrari, an epidemiologist at Pennsylvania State University's Center for Infectious disease Dynamics in University Park. A perfectly coordinated global campaign could take wiped out COVID-19, he says, at least theoretically. "Information technology's a technically viable affair, only in reality information technology's very unlikely that we will reach that on a global calibration," he says. In that location are huge variations in the efficiency of vaccine ringlet-outs between countries (encounter 'Disparities in distribution'), and fifty-fifty within them.

Israel began vaccinating its citizens in December 2020, and thanks in role to a deal with Pfizer–BioNTech to share data in exchange for vaccine doses, it currently leads the world in terms of roll-out. Early on in the campaign, health workers were vaccinating more than 1% of State of israel'southward population every day, says Dvir Aran, a biomedical data scientist at the Technion — Israel Plant of Engineering science in Haifa. As of mid-March, effectually 50% of the country'south population has been fully vaccinated with the 2 doses required for protection. "Now the problem is that young people don't desire to become their shots," Aran says, so local authorities are enticing them with things such equally free pizza and beer. Meanwhile, Israel's neighbours Lebanese republic, Syria, Jordan and Egypt have yet to vaccinate even 1% of their respective populations.

Across the U.s., access to vaccines has been uneven. Some states, such as Georgia and Utah, have fully vaccinated less than 10% of their populations, whereas Alaska and New Mexico have fully vaccinated more than 16%.

In most countries, vaccine distribution is stratified by age, with priority given to older people, who are at the highest chance of dying from COVID-nineteen. When and whether there will be a vaccine canonical for children, however, remains to be seen. Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna have now enrolled teens in clinical trials of their vaccines, and the Oxford–AstraZeneca and Sinovac Biotech vaccines are being tested in children as young as three. But results are still months away. If it's not possible to vaccinate children, many more adults would need to be immunized to achieve herd immunity, Bansal says. (Those aged 16 and older can receive the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine, just other vaccines are approved only for ages 18 and upward.) In the Us, for example, 24% of people are under 18 years onetime (according to 2010 demography data). If nigh under-18s can't receive the vaccine, 100% of over-18s volition have to be vaccinated to reach 76% amnesty in the population.

Another important thing to consider, Bansal says, is the geographical structure of herd immunity. "No community is an island, and the landscape of amnesty that surrounds a customs actually matters," she says. COVID-19 has occurred in clusters beyond the United States as a consequence of people'south behaviour or local policies. Previous vaccination efforts suggest that uptake volition tend to cluster geographically, too, Bansal adds. Localized resistance to the measles vaccination, for example, has resulted in small pockets of illness resurgence. "Geographic clustering is going to make the path to herd immunity a lot less of a directly line, and essentially ways we'll be playing a game of whack-a-mole with COVID outbreaks." Even for a land with high vaccination rates, such as Israel, if surrounding countries haven't done the same and populations are able to mix, the potential for new outbreaks remains.

New variants alter the herd-amnesty equation

Fifty-fifty equally vaccine gyre-out plans face up distribution and allocation hurdles, new variants of SARS-CoV-2 are sprouting up that might be more than transmissible and resistant to vaccines. "We're in a race with the new variants," says Sara Del Valle, a mathematical and computational epidemiologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. The longer information technology takes to stalk transmission of the virus, the more time these variants accept to emerge and spread, she says.

What's happening in Brazil offers a cautionary tale. Research published in Science suggests that the slowdown of COVID-19 in the city of Manaus between May and October might have been owing to herd-immunity effects (L. F. Buss et al. Science 371, 288–292; 2021). The area had been severely hit by the disease, and immunologist Ester Sabino at the Academy of São Paulo, Brazil, and her colleagues calculated that more than than sixty% of the population had been infected by June 2020. According to some estimates, that should have been enough to get the population to the herd-immunity threshold, but in January Manaus saw a huge resurgence in cases. This fasten happened subsequently the emergence of a new variant known as P.1, which suggests that previous infections did not confer wide protection to the virus. "In January, 100% of the cases in Manaus were caused by P.i," Sabino says. Scarpino suspects that the threescore% effigy might have been an overestimate. All the same, he says, "Yous nonetheless have resurgence in the confront of a loftier level of immunity."

There's another problem to contend with as immunity grows in a population, Ferrari says. College rates of immunity can create selective pressure level, which would favour variants that are able to infect people who have been immunized. Vaccinating rapidly and thoroughly can prevent a new variant from gaining a foothold. But once more, the unevenness of vaccine roll-outs creates a challenge, Ferrari says. "You've got a fair bit of immunity, but you still have a fair bit of disease, and you're stuck in the heart." Vaccines volition almost inevitably create new evolutionary pressures that produce variants, which is a skillful reason to build infrastructure and processes to monitor for them, he adds.

Immunity might not terminal forever

Calculations for herd amnesty consider ii sources of individual immunity — vaccines and natural infection. People who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 seem to develop some immunity to the virus, only how long that lasts remains a question, Bansal says. Given what's known about other coronaviruses and the preliminary show for SARS-CoV-2, information technology seems that infection-associated immunity wanes over time, and so that needs to exist factored in to calculations. "We're still defective conclusive information on waning immunity, just we do know it'southward non nada and not 100," Bansal says.

Modellers won't be able to count everybody who'due south been infected when computing how close a population has come to the herd-immunity threshold. And they'll accept to account for the fact that the vaccines are non 100% effective. If infection-based immunity lasts only for something like months, that provides a tight deadline for delivering vaccines. Information technology will also be of import to understand how long vaccine-based amnesty lasts, and whether boosters are necessary over time. For both these reasons, COVID-19 could get like the flu.

Vaccines might change human behaviour

At current vaccination rates, Israel is closing in on the theoretical herd-amnesty threshold, Aran says. The problem is that, as more people are vaccinated, they will increase their interactions, and that changes the herd-immunity equation, which relies in part on how many people are being exposed to the virus. "The vaccine is not bulletproof," he says. Imagine that a vaccine offers xc% protection: "If before the vaccine you lot met at most one person, and now with vaccines you encounter ten people, you're back to square one."

The most challenging aspects of modelling COVID-19 are the sociological components, Meyers says. "What we know near man behaviour up until now is really thrown out of the window because we are living in unprecedented times and behaving in unprecedented ways." Meyers and others are trying to adjust their models on the fly to account for shifts in behaviours such equally mask wearing and social distancing.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions will proceed to play a crucial part in keeping cases downwardly, Del Valle says. The whole point is to break the manual path, she says, and limiting social contact and continuing protective behaviours such as masking can help to reduce the spread of new variants while vaccines are rolling out.

Simply it's going to exist difficult to stop people reverting to pre-pandemic behaviour. Texas and some other US land governments are already lifting mask mandates, even though substantial proportions of their populations remain unprotected. It's frustrating to see people easing off these protective behaviours right at present, Scarpino says, because standing with measures that seem to be working, such as limiting indoor gatherings, could go a long way to helping end the pandemic. The herd-immunity threshold is "not a 'nosotros're safe' threshold, it's a 'we're safer' threshold", Scarpino says. Even after the threshold has been passed, isolated outbreaks volition nonetheless occur.

To sympathise the additive effects of behaviour and immunity, consider that this flu flavour has been unusually balmy. "Influenza is probably not less transmissible than COVID-nineteen," Scarpino says. "Almost certainly, the reason why flu did not show up this year is because we typically have near 30% of the population immune because they've been infected in previous years, and you get vaccination covering maybe another 30%. So you're probably sitting at lx% or so immune." Add mask wearing and social distancing, and "the flu only tin't make it", Scarpino says. This back-of-the-envelope calculation shows how behaviour can alter the equation, and why more people would need to be immunized to accomplish herd amnesty as people stop practising behaviours such every bit social distancing.

Ending transmission of the virus is one way to return to normal. But another could be preventing severe affliction and decease, says Stefan Flasche, a vaccine epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Given what is known about COVID-19 so far, "reaching herd immunity through vaccines lonely is going to be rather unlikely", he says. It's time for more than realistic expectations. The vaccine is "an absolutely amazing development", just information technology's unlikely to completely halt the spread, so we need to think of how we can alive with the virus, Flasche says. This isn't as grim equally it might audio. Even without herd immunity, the ability to vaccinate vulnerable people seems to be reducing hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19. The disease might non disappear whatever time soon, only its prominence is probable to wane.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00728-2

0 Response to "If Vaccinations Are So Effective How Come Peoole in Their 50s Need to Get It Again?"

Post a Comment